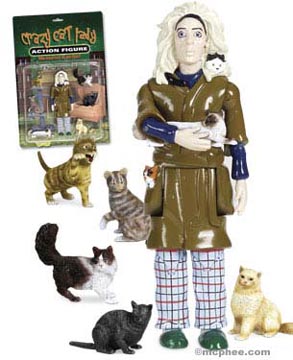

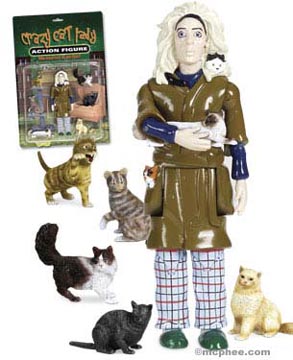

My subscription to Psychiatric Times always has something interesting associated with it. Bottom line: the stereotype of the crazy, isolated cat lady may be dead-on true.

Environmental Factors in Schizophrenia Three epidemiological studies bolster the evidence for infectious

and social influences on the development of schizophrenia. Swedish

national registers show an association between psychotic illness

and childhood viral, but not bacterial, infections of the central

nervous system (CNS). Dalman et al. (p.

59) analyzed hospitalizations

for CNS infections before age 13 and psychotic illnesses from

age 14 onward in children born during 1973–1985. Psychosis

risk was almost tripled by childhood mumps exposure and was

over 16 times as high after cytomegalovirus exposure. Using

blood samples collected routinely by the U.S. military, Niebuhr

et al. (p.

99) confirmed a relationship between schizophrenia

and

toxoplasmosis. IgG antibodies to

Toxoplasma gondii were

compared in service members medically discharged with schizophrenia

between 1992 and 2001 and matched healthy subjects. The antibody

level was nearly 25% higher for the subjects with schizophrenia

in the 6 months preceding the diagnosis or after it. Dr. Alan

Brown examines these two studies in an editorial on p.

7. Veling

et al. (p.

66) identified social isolation as a risk factor

for

psychotic disorders among immigrants in The Hague. City

records provided the ethnic backgrounds and locations of residents

who received a first diagnosis of psychotic disorder over 7

years. Immigrants in neighborhoods with high densities of immigrants

from the same country had a rate of psychotic illness similar

to that of native Dutch residents, but those in neighborhoods

with low densities of the same ethnic group had a rate more

than double that for the Dutch.

Susan Jacoby’s The Age of American Unreason is my weekend reading. After an initial burst of polemic that was perhaps too careless about the roles of new information technologies and games in modern idea formation, she settles into a detailed analysis of the history of reason, science, pseudoscience and anti-intellectualism in American life. Almost as soon as Huxley hit the lecture circuit with a discussion of Darwinian evolution, social and economic theorists began an expansive integration of the core algorithm into their theories, justifying racism, colonialism, laissez-faire capitalism and, later, eugenics from a loosely critical reading of Darwin.

Susan Jacoby’s The Age of American Unreason is my weekend reading. After an initial burst of polemic that was perhaps too careless about the roles of new information technologies and games in modern idea formation, she settles into a detailed analysis of the history of reason, science, pseudoscience and anti-intellectualism in American life. Almost as soon as Huxley hit the lecture circuit with a discussion of Darwinian evolution, social and economic theorists began an expansive integration of the core algorithm into their theories, justifying racism, colonialism, laissez-faire capitalism and, later, eugenics from a loosely critical reading of Darwin.